Magnolia URLs and location tracking

On this page we look at typical Magnolia URLs and learn how the fragment part of a URL makes location tracking possible. With fragments you can pinpoint detailed locations in the system. Users can bookmark their favorite apps, pages and nodes.

Parts of a URL

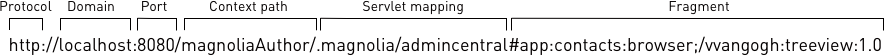

A typical URL in the Magnolia back-end looks like this:

Parts of a URL:

-

Protocol:

httporhttps. -

Domain: Domain name as mapped in the site definition.

-

Port: Port number.

-

Context path: In a Magnolia URL the context path represents a Web application such as

magnoliaAuthorormagnoliaPublic. -

Servlet mapping : Identifies the servlet that should respond to the request.

-

Fragment : Keeps track of an app’s internal state. Identifies the name of the app, the subapp, and optionally a path.

Servlet mapping

A servlet responds to a request. Servlets are mapped in the

servlet

filter chain. By convention, a Magnolia servlet mapping starts with the

dot character, for example /.magnolia/admincentral for AdminCentral

resources or /.rest for REST resources.

A REST URL is a good example of complex

servlet mapping. The URL requests the page /travel/about. The servlet

mapping part contains detailed information about the requested resource.

Parts of a servlet mapping:

-

Servlet: The first part of the mapping identifies the servlet, in this case

/.rest. -

Endpoint: Identifies the REST endpoint where the request is issued:

nodes,propertiesorcommands. -

Version: REST Web services are versioned. The version number is built into the service URL.

-

Workspace: Identifies which workspace in the

magnoliarepository has the requested content. -

Node path: Location of the content in the workspace.

Fragment

Fragment is the part of the URL that starts with the hash character #.

In AdminCentral URLs, the fragment keeps track of an app’s internal

state. It identifies the name of the app, the subapp that is open, and

optionally a path to the content that is operated on. In public URLs the

fragment identifies an anchor.

The parts that come after the hash are separated with a colon :

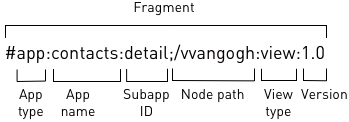

Example: This fragment identifies the

Contacts app. The detail subapp is

currently open. The user is viewing version 1.0 of the node /vvangogh

Parts of a fragment:

-

App type: The type is

appfor normal apps andshellfor the special Shell apps: App Launcher, Tasks and Messages. For your own apps, this part will always beapp. -

App name: Name of the app as configured in the app descriptor. Apps are named in a predictable way: Pages is

pages, Assets isassetsand so on. Magnolia uses the app name to identify the app across the system. -

Subapp ID: ID of the subapp as configured in the subapp descriptor. Subapps are displayed to users as tabs. Every app has at least one subapp. In a content app, subapps are called

browseranddetail. In custom apps, you can name your subapps as you want. Magnolia recommends that you name your main subappmainfor consistency. Themainsubapp can be the only subapp if the app does not provide any other subapps. -

Node path: Path to the node being operated on.

-

View type:

edit,view(preview),treeview,listview,thumbnailvieworsearchview. -

Version: Version of the node.

Example fragments

App launcher shell app.

#shell:applauncherPages app with the browser subapp open. The /travel/about page is

currently selected in the treeview.

#app:pages:browser;/travel/about:treeviewPages app with an detail subapp open. The /travel/about page is being

edited.

#app:pages:detail;/travel/about:editPages app with a detail subapp open. The /travel/about page is being

previewed. The view parameter instructs the app to display the page in

preview mode.

#app:pages:detail;/travel/about:viewSubapp ID and its parameters

The subapp ID part of the fragment holds the subapp’s name and optional

parameters. Each subapp ID is unique within the app. This allows the

system to recognize a tab that is already open and bring that tab into

focus rather than open a duplicate. For example, when the Pages app

opens a detail subapp it assigns the subapp a unique ID consisting of

the subapp name (detail) and the path to the page (/travel/about).

If the user already has the page open the app brings the tab into focus

when it is requested.

#app:pages:detail;/travel/aboutA node path is the most common example of a parameter. The path

identifies the node being viewed or edited, for example /travel/about.

The subapp ID and the node path are separated with a semicolon. We

cannot use the colon character here as it would break the token.

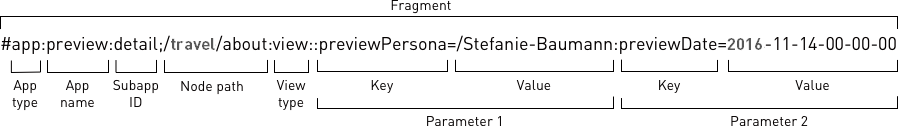

Custom parameters inside the fragment

Here is an example of custom parameters in the fragment. The Preview app is being used to preview personalized content.

Parameters:

-

previewPersonaassigns a persona who represents the target audience. -

previewDateassigns a date.

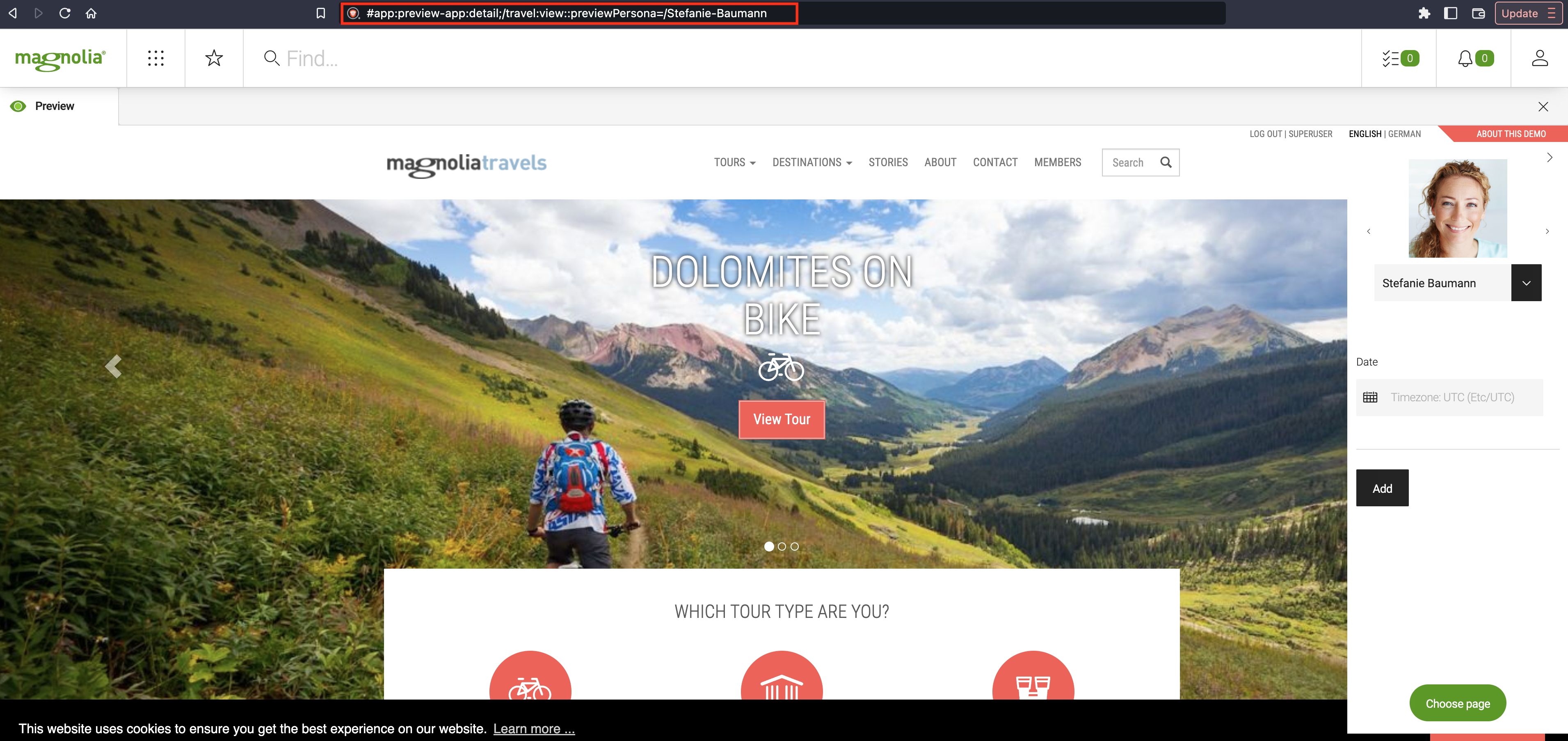

Here’s what the Preview app looks like in the browser.

Selectors

A selector is a part of a URI between the first selector delimiter ~

(tilde) and the last selector delimiter.

Selectors are similar to query parameters in that they allow you to pass

information to a servlet. The difference is that a query parameter sends

input to be processed whereas a selector describes how you want to

receive the requested resource. In this respect selectors are like

extensions. The extension .html specifies that you want to receive the

resource as an HTML document. The selector Culture specifies that

you want a list of tours about culture. It is still the same resource

(tours list page) but instead of all tours you want it filtered by the

category Culture.

For more on request parameters vs. selectors see Selectors and Request Parameters: Getting it Straight (page snapshot at archive.org).

Magnolia uses the tilde character ~ as a selector delimiter. In other

systems such as Apache Sling you may see the dot character . used as a

delimiter. We can’t use the dot in Magnolia because the

JCR

specification allows dots in node names, and consequently in URIs, with

the single limitation that a dot cannot be the first character. This

means a page page.one, a document magnolia.flyer.pdf, an a

JavaScript file jquery.tabtree are all perfectly valid node names and

must work in URIs.

The info.magnolia.cms.core.Path class sets ~ (tilde) as

the delimiter in the SELECTOR_DELIMITER constant (String).

Splitting selectors

The whole selector can be split into several selectors separated from

each other by the same delimiter ~ (tilde):

-

Whole selector:

Culturea=1b=2 -

Selector 1:

Culture -

Selector 2:

a=1 -

Selector 3:

b=2

Getting and setting selectors

A selector can also be in the form name=value. For example in

/mypagefoo=bar.html where foo=bar is a name-value selector.

Name-value selectors are exposed by

MgnlContext.getAttribute(selectorName) and have a local scope

similar to HttpServletRequest scope. In the example,

MgnlContext.getAttribute("foo") will return the String bar whereas

MgnlContext.getAttribute("foo", Context.SESSION_SCOPE) or

MgnlContext.getAttribute("foo", Context.APPLICATION_SCOPE) will return

null.

AggregationState

This class exposes some methods to set and get selectors.

-

setSelector(String selector)is currently used byinfo.magnolia.cms.filters.RepositoryMappingFilterwhere the request URI is parsed and the selector part extracted. -

String getSelector()returns the whole selector. I.e given the URIhttp://myserver/mypagexfoo=bar~.htmlthis method will return the String x~foo=bar -

String[] getSelectors()returns the selector split into its discrete elements. I.e given the URIhttp://myserver/mypagexfoo=bar~.htmlthis method will return an array of two elements containing thexand thefoo=barString(s)

Creating a browsing history with fragments

The URL fragment can pinpoint very fine-grained locations in the system such as a particular page or configuration node. This makes it possible to build a detailed browsing history. Navigating a browsing history via fragments is not a unique concept. We adopted it from the Google Web Toolkit (GWT):

For each page that is to be navigable in the history, the application should generate a unique history token. A token is simply a string that the application can parse to return to a particular state. This token will be saved in browser history as a URL fragment (in the location bar, after the

#), and this fragment is passed back to the application when the user goes back or forward in history, or follows a link.

Moving back and forward in browser history

This is how modern Web applications should work: rather than prevent the user from clicking the Back and Forward buttons, let them do what feels intuitive. If clicking Back seems like the right thing to do to get to the previous state then the application should support that feeling. Using the URL fragment allows the user to use the browser’s own back and forward functionality.